Sundays with the Morgans

Welcome to another excerpt from, Libby Morgan: Reunion and a bit of Foundling Hospital history.

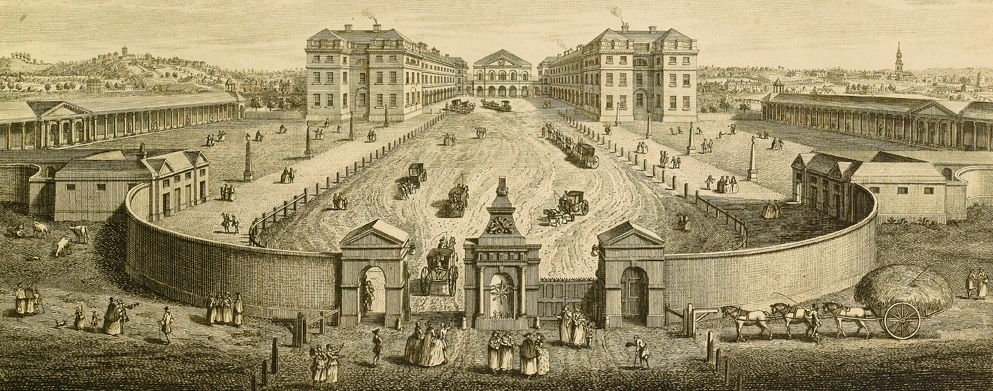

This week, I want to share with you a very special place in London, England called the Foundling Hospital – it is an integral part of my novel and the basis of the mystery Libby uncovers while crossing the Atlantic.

Let’s begin with the excerpt from the novel – in which Mother Morgan is recounting to Libby the fate of her first-born, twin daughters.

Read the book, you’ll understand why they are different.

“When I begged her to tell us where in London she had taken the babes, she paused long before answering. ‘I took them to Bloomsbury Fields, Mum!’ she whispered with downcast eyes, and my own mother let out a cry of shock. I felt sick to my stomach, though I didn’t understand the implications of the name, so I asked Mother, who clearly knew the place, what it meant. She said in a voice I will never forget, ‘It is where unwanted babes are left by mothers who cannot care for them.’ She had left my babes at the Foundling Hospital. ‘My conscience would not allow me to leave them unidentifiable,’ Dwyn said at last. ‘I left them with a bit of this fabric, and though I cannot write so as to have left them with a note, I told the nurse that their mother would collect them as soon as she was able and to please keep them safe.’ She held out to me a piece of pink printed cotton and said that I could collect the babes as long as I had this piece of fabric.”

The London Foundling Hospital spurs in me a wide range of sentiments, which begins with great sorrow and only after a very twisted roller-coaster ride of emotions, eventually emerges into great joy. How is that possible, you ask? Let’s takes a closer examination of the nearly two-hundred-seventy-five-year-old establishment and you will see how such a place can arouse these feelings.

Established in 1739, the Foundling Hospital is England’s oldest children’s charity and has been in continual operation since it’s foundation – today it is operated by the modern charity, Coram. It has been a place where over-remiss mothers have abandoned their unwanted babes; it has been a place where desperate parents have lovingly left their cherished child because they could not feed one more mouth. In one simple phrase. . . It is a place for the loved and a place for the lost. The Hospital was renown for its documentation of the children left in their care. The registration forms (or billets, as they were called) were individually numbered and contained detailed information about each child including sex, distinguishing marks, and descriptions of the clothing they were wearing when left at the Hospital. The basic procedure was to collect a token of some sort from the mother (or whoever left the child); this token could have been a note, a letter, or a small object. Often, a swatch of fabric, stitchery or ribbon was used as the token. This token was kept with the billet for identification purposes and, should the parents’ circumstances change, they could reclaim the babe with the matching piece of fabric or token. Sadly, very few children were reclaimed.

Established in 1739, the Foundling Hospital is England’s oldest children’s charity and has been in continual operation since it’s foundation – today it is operated by the modern charity, Coram. It has been a place where over-remiss mothers have abandoned their unwanted babes; it has been a place where desperate parents have lovingly left their cherished child because they could not feed one more mouth. In one simple phrase. . . It is a place for the loved and a place for the lost. The Hospital was renown for its documentation of the children left in their care. The registration forms (or billets, as they were called) were individually numbered and contained detailed information about each child including sex, distinguishing marks, and descriptions of the clothing they were wearing when left at the Hospital. The basic procedure was to collect a token of some sort from the mother (or whoever left the child); this token could have been a note, a letter, or a small object. Often, a swatch of fabric, stitchery or ribbon was used as the token. This token was kept with the billet for identification purposes and, should the parents’ circumstances change, they could reclaim the babe with the matching piece of fabric or token. Sadly, very few children were reclaimed.

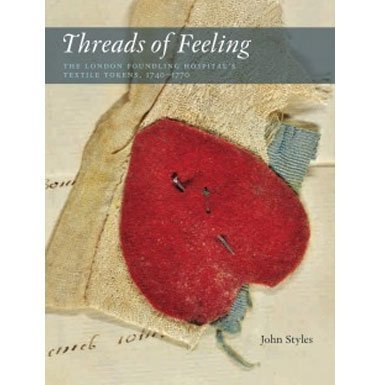

In 2010, John Styles wrote a fabulous book, Thread of Feelings: The London Foundling Hospital’s Textile Tokens, 1740-1770, that not only documents the history of the Hospital, but it gives us textile lovers a closer look at the textiles found in the billet-book archives. Styles describes the Hospital archives as “Britian’s largest collection of everyday textiles” which contained “some 5,000 rare, beautiful, mundane and moving scraps of fabric.” These fabric scraps are instrumental in the research of the common clothing worn by everyday people – clothing which rarely survived and was almost never kept as treasure or purchased by museums and collectors.

In 2010, John Styles wrote a fabulous book, Thread of Feelings: The London Foundling Hospital’s Textile Tokens, 1740-1770, that not only documents the history of the Hospital, but it gives us textile lovers a closer look at the textiles found in the billet-book archives. Styles describes the Hospital archives as “Britian’s largest collection of everyday textiles” which contained “some 5,000 rare, beautiful, mundane and moving scraps of fabric.” These fabric scraps are instrumental in the research of the common clothing worn by everyday people – clothing which rarely survived and was almost never kept as treasure or purchased by museums and collectors.

To see the bits and pieces of fabric that were left with, or taken from the clothing worn by the orphaned children tears at my heart. I just close my eyes and I can envision the scene of the poor, despondent mother standing at the gates trying to decide if what she is doing is the right decision. Desperate and filled with sorrow, I see her offer her newborn babe over to the nurse on duty; but needing to feel just the tiniest bit of connection with her child, she quickly rips a piece of her skirt and gives it over as her token. “One day,” she lies to herself, “I will come back.” The whole scene is so bereft of happiness and shrouded in pain – and when I consider the number of children that were left at the gates every year, I am sure there is nothing in which to find joy – yet there is a ray of hope in the heartbreak. The Foundling Hospital did much to save the lives of the children left in their care; to educate them, even vaccinate them in later years and provided them with a future better than they may have had with their own mothers. For many children, life in the Foundling Hospital was a significant improvement over the certain starvation and death they faced at the hands of severe poverty. It is this knowledge of goodness and charity given to the neediest of humanity that makes me look upon those bits of fabric with a different eye. I try not to view the tragic aspect of a mother separated from her babe; I look for the hope and I see the possibility that some of the children grew up and lived fulfilling lives. And I am joyful in knowing that due to the efforts of the staff at the hospital, some broken hearts were actually reunited simply because of a tiny piece of matching fabric.

To see the bits and pieces of fabric that were left with, or taken from the clothing worn by the orphaned children tears at my heart. I just close my eyes and I can envision the scene of the poor, despondent mother standing at the gates trying to decide if what she is doing is the right decision. Desperate and filled with sorrow, I see her offer her newborn babe over to the nurse on duty; but needing to feel just the tiniest bit of connection with her child, she quickly rips a piece of her skirt and gives it over as her token. “One day,” she lies to herself, “I will come back.” The whole scene is so bereft of happiness and shrouded in pain – and when I consider the number of children that were left at the gates every year, I am sure there is nothing in which to find joy – yet there is a ray of hope in the heartbreak. The Foundling Hospital did much to save the lives of the children left in their care; to educate them, even vaccinate them in later years and provided them with a future better than they may have had with their own mothers. For many children, life in the Foundling Hospital was a significant improvement over the certain starvation and death they faced at the hands of severe poverty. It is this knowledge of goodness and charity given to the neediest of humanity that makes me look upon those bits of fabric with a different eye. I try not to view the tragic aspect of a mother separated from her babe; I look for the hope and I see the possibility that some of the children grew up and lived fulfilling lives. And I am joyful in knowing that due to the efforts of the staff at the hospital, some broken hearts were actually reunited simply because of a tiny piece of matching fabric.

I hope that I have sparked an interest in the Foundling Hospital, Threads of Feeling, and of course, Libby Morgan: Reunion. There is a great deal of information out on the web and a simple “google” will open the history pages for you. The Threads of Feeling Facebook page is also a great resource – like it here.